Explore the Beauty of Rationality: Naoshima Chichu Art Museum

Disclaimer: This is a translated version of https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/qh0BNsLY8fu7wvaIhRcfjQ

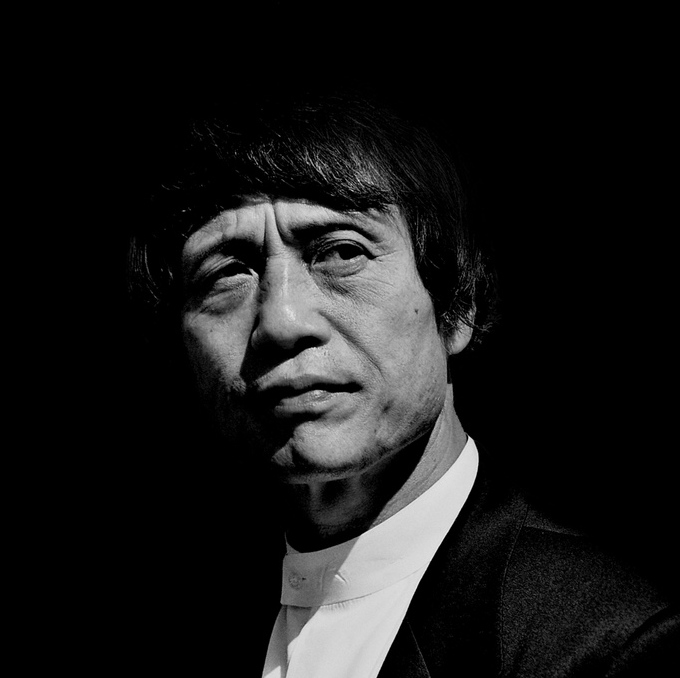

When I visited the Seto Inland Sea in March last year, I went to Naoshima Island. Even though it wasn’t during the Setouchi Art Festival, entry to the Chichu Art Museum still required a timed admission ticket. Unfortunately, due to certain circumstances, I didn’t pay a visit. As a result, it remained one of my largest regrets from that trip. This year, I returned to Naoshima and finally got to experience the architectural masterpiece by Tadao Ando—the Chichu Art Museum—redeeming that missed opportunity.

From an aerial perspective, the rooftop of the Chichu Art Museum appears as a series of geometrical shapes—square, rectangle, and triangle—blending elegantly into the lush greenery. Since the museum is designed to exist underground, these shapes, which serve as natural sources of illumination for the entire museum, look like shadows projected onto the forest from the sky. This creates a sense of harmony with nature while maintaining a minimalist aesthetic.

The Chichu Art Museum houses only three artists’ works: Claude Monet, the father of Impressionism; contemporary artist Walter De Maria; and James Turrell.

If you haven’t seen the works inside, the geometric shapes selected by Tadao Ando might appear to be purely about visual beauty. However, after visiting, you’ll realize that these shapes integrate seamlessly with the artworks displayed within. As a result, the building itself and its aerial geometry become part of the museum’s artistic expression. In this way, Tadao Ando naturally becomes the fourth artist of the museum.

Entering the Chichu Art Museum feels like stepping into Tadao Ando’s personal world. Ando’s choice of materials is simple and consistent across his projects: concrete, glass, wood, and iron. This museum is no exception. But how does he imbue such “cold” materials with warmth? Ando achieves this through thoughtful architectural structures, where natural light filters through precisely placed openings to create projections and reflections on the walls. The gray concrete takes on different hues under varying light conditions.

The artistic language of Ando’s design reflects his rational approach: every visible form adheres to strict geometric rules—straight lines, rectangles, and rhombuses. There are no arbitrary curves, no complexity—only pure minimalism.

The artworks complement this aesthetic. In Walter De Maria’s room, geometrical shapes dominate. In James Turrell’s exhibition spaces, the boundaries of the artworks are also strictly rectangular.

The only exception is Monet’s work. Those familiar with Western modern art history know Monet as the father of Impressionism. A hallmark of Impressionism is its vivid depiction of changing light and color, focusing on expression rather than realism. Monet’s Water Lilies series perfectly illustrates this. Perhaps choosing to display Monet’s work was a personal decision of Ando—maybe he particularly admired Monet?

In Walter De Maria’s room, a massive marble sphere dominates the space, surrounded by tall, gold geometric columns. It creates a feeling of serenity. On closer observation, you’ll find that the outlines of these gold forms adhere strictly to geometrical shapes. The accompanying notes suggest: “The entire artwork changes with the light.” Under carefully designed lighting, the shadows cast by these shapes on the walls are also geometrical, maintaining consistency from any perspective.

The gold leaf covering the geometric structures reflects the sun’s changing position throughout the day, creating different perspectives and effects. This interplay with light transforms the static objects of this room into a dynamic art installation—one that feels familiar in modern art expressions. What’s fascinating is how De Maria uses natural light to achieve this transformation without relying on technological interventions.

James Turrell’s works are even more intriguing. His Afrum, Pale Blue creates a dynamic illusion, where a square seems to rotate as the viewer’s perspective changes. Open Sky inspired whimsical speculation with a fellow visitor: Was the ceiling an open roof, LED, or something else entirely? The exhibition notes list LED as a material, yet the effect mimics an open sky so purely that we wondered how the heavy concrete roof seemed to disappear. Open Field offers another surprise: what looks like a flat shape on the wall turns out to be an immersive, three-dimensional space. Guided by the staff, you enter, only to discover layers of nested spaces—a visual game played between Turrell and the viewer.

Final Words

For me, few contemporary artworks deliver such a clear sense of revelation. Contemporary art must balance innovation with accessibility—creating something new while ensuring the audience can understand it. This is a challenging duality. Since Duchamp’s Fountain, contemporary art has increasingly ventured into the abstract, often leaving audiences perplexed.

I’m not criticizing such art but observing that if a work fails to establish any meaningful interaction with viewers, it risks alienating them. People might question their own ability to appreciate art: “Can I even understand this piece?” That’s not an ideal direction.

In the Chichu Art Museum, the artworks engage with viewers on multiple levels. Stepping out of each exhibition space and looking back at the building as a whole, you’re struck again by the brilliance of its design—every scene, every angle reflects geometric order and radiates a rational beauty. This deepened my admiration for the Chichu Art Museum.

I hope one day you’ll also have the chance to see this artistic sanctuary on a small island in the distant Seto Inland Sea.

For more insights into Turrell’s works, refer to this article: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/25320554. It explains how clever use of wedges achieves a surreal effect, confirming my suspicions about Open Sky.